Dr Catherine Spencer, lecturer in Art History at the University of St Andrews writes about the inspiring work of Maud Sulter. Catherine’s research and teaching focuses on art since the 1960s in the US, Latin America and Europe, particularly in relation to performance; technologies of mediation; internationalism and transnationalism; sociology, psychology and psychoanalysis; and sexuality, gender and histories of feminist practice.

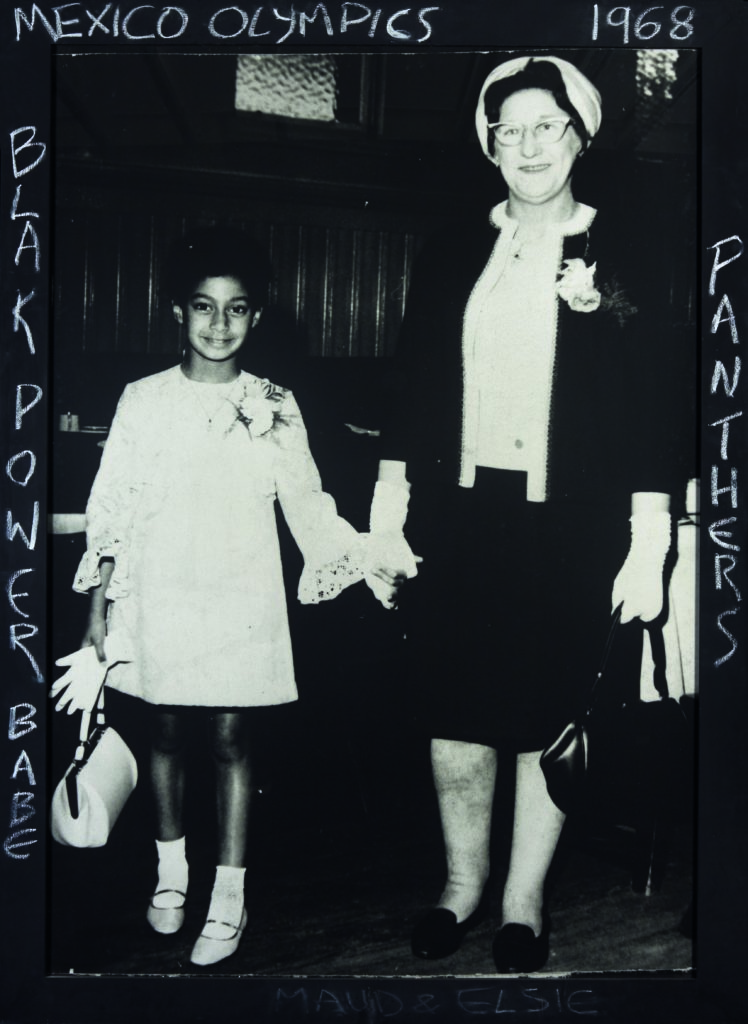

The writer, artist and curator Maud Sulter’s Significant Others series (1993) comprises nine large-scale silver gelatin photographic prints, each measuring just over one metre by one-and-a-half metres. They are presented in bespoke wooden frames which the artist painted black and annotated with chalk, sometimes including the individual work’s title together with dates relating to the events captured. All are enlargements of what were originally much smaller snapshots taken from Sulter’s family archive, intimately embedding the series in the artist’s longstanding creative exploration of her Scottish and Ghanaian heritage. Sulter (1960–2008) was born in Glasgow, and despite moving to London aged 17 to pursue her studies at the London College of Fashion, maintained close ties with Scotland throughout her career, before returning to the country later in life and spending her last years in Dumfries. Sulter wrote poetry in Scots vernacular and old Scots, exhibited at institutions including the City Arts Centre and the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh, and worked with the Scottish Poetry Library on photographic portraits of Scottish poets in 2003–4. Significant Others relates to a number of key concerns in Sulter’s practice, notably the centuries of rich diasporic exchange between Europe and Africa, black feminist thought and activism, and the pioneering interrogations of history and representation forged by many artists associated with the Black Arts Movement in Britain during the 1980s. Significant Others moreover manifests an aspect of Sulter’s work that remains under-studied: her use of family photography, and exploration of both its ideological and affectual qualities.

Sulter created Significant Others during a period which the art historian Deborah Cherry has identified as a ‘highly productive’ one for the artist, as she worked freely across photo montage, film and installation in the mid-1990s.[i] This built in turn on an efflorescence of activity during the preceding decade, including participating in the ground-breaking exhibition The Thin Black Line (1985) at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, curated by the artist Lubaina Himid. The show featured eleven black women artists who came together under a shared conceptualisation of blackness as a political identity, while working from a variety of perspectives and across a range of media. As Himid has stressed:

It suited us to show alongside each other, presenting a whole variety of beliefs, life choices and philosophical perspectives. We exhibited in this way to make visible our richness of vision. We did not all think about audiences in the same way or use materials in the same way.[ii]

Sulter’s specific approach within the heterogenous field encompassed by the Black Arts Movement in Britain involved adopting the portmanteau terms ‘blackwoman’ and ‘blackwomen,’ in order to signal her intersectional black feminist politics. These terms appear in the titles of her poetry collection As a Blackwoman (1985), and Passion: Discourses on Blackwomen’s Creativity (1989), an important anthology that Sulter edited. Sulter’s engagement with family photography ran in parallel with, and was deeply informed by, these endeavours. In 1989 she produced the poetry collection Zabat: Poetics of a Family Tree. This relates in turn to another large-scale photographic series from the same year, also entitled Zabat, which re-imagines the nine muses – represented in the Eurocentric art historical canon as white women – as black women creatives and thinkers. This body of work signals how Sulter’s commitment to black feminism and diasporic imaging and imaginings were closely intertwined.

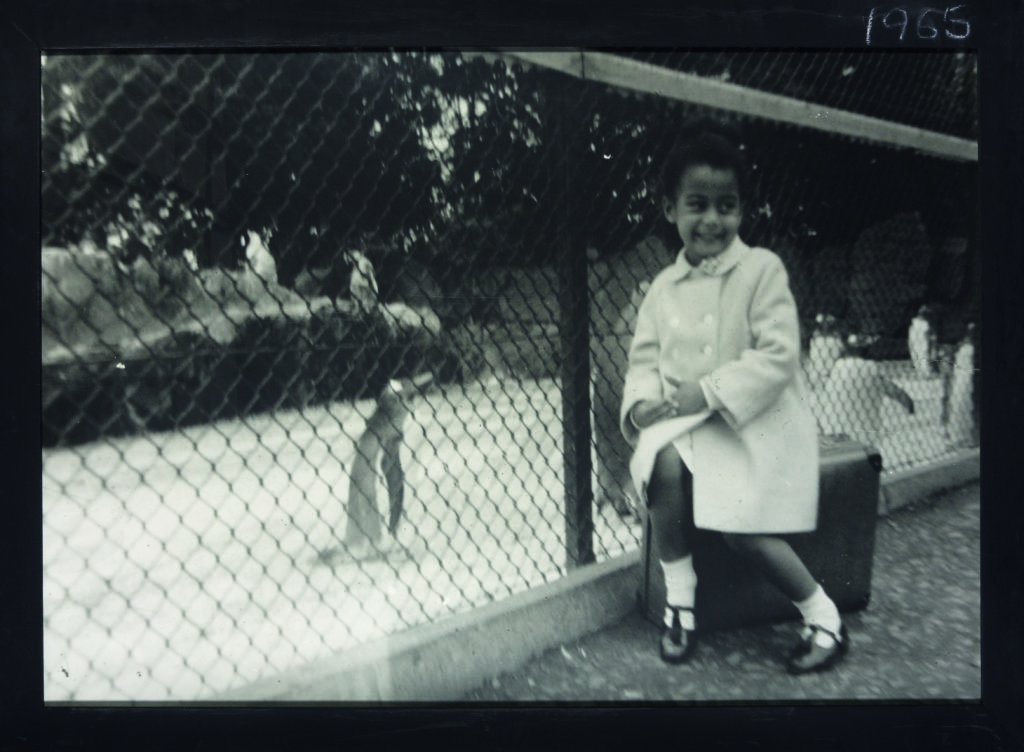

Significant Others can be understood as a statement of self-imaging, in which the self is depicted as intrinsically relational, sustained by generational links of familial love and support. These are the ‘significant others’ invoked by the overarching title: the parents, grandparents and extended relatives who people Sulter’s Scottish photographic family archive. Sulter herself appears in four of the nine images, including Snap I, which reproduces one of Sulter’s favourite childhood photographs. Taken by a street photographer, it captures the artist as a baby propped up in a pram, with a parrot balancing cheekily on the hood. Best Buddies shows Sulter playing on the beach with her maternal grandfather, who wrote poetry and experimented with amateur photography, providing an important early influence for her subsequent career. C’est moi is a solo photograph of Sulter at Edinburgh Zoo, sitting in front of the penguin enclosure. The title of this image in particular constitutes a statement of becoming, of laying claim to identity: ‘this is me’.

But perhaps the most powerful image in this respect is Maud and Elsie, a photograph of Sulter clasping hands tightly with her mother, who worked as a conductor on Glasgow’s trams. Both are smartly dressed and smiling, with sprays of flowers pinned to their clothes, suggesting a formal family occasion like a wedding or christening. The implications of this celebratory dynamic, however, are dramatically expanded by the chalked words that Sulter has written on the wooden frame: ‘Mexico Olympics,’ ‘1968,’ ‘Blak Power Babe,’ and ‘Panthers’. These powerfully triangulate the revolutionary politics of the Black Power movement which emerged in the United States during the 1960s, its emblematic expression in the formation of the Black Panther Party, and the iconic protest at the 1968 Mexico Olympics by the gold and bronze-medal winning 200-metre sprint athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who raised their fists in Black Power salutes on the podium. Connected with the title ‘Maud & Elsie’ along the bottom of the frame, Sulter points to her vital formation through networks of black diasporic political thought spanning Africa, the Americas and Europe. The resulting image underscores the need to understand Scotland’s history as fundamentally bound up with continued struggle and resistance in the ongoing aftermath of slavery, imperialism and colonialism. It offers a visual manifestation of Sulter’s assertion: ‘I believe Blackwomen’s Creativity to be revolutionary in its potential. It confronts racism, sexism, privilege, abuse, but tries soulfully not to lose its integrity.’[iii]

The annotations that Sulter makes on the frames across the Significant Others series provide both a way of training the viewer’s attention on the image, and of excavating layers of embedded meaning. In a 1992 interview with Mark Haworth-Booth, Sulter reflected:

I feel that we’re surrounded by photographic images – we engage with them in newspapers and magazines, on billboards, we read film, we read television images, and so it’s a very immediate process in terms of its production; and it’s a very immediate process in terms of catching the viewer’s attention in the first moment. But obviously the challenge is then to get beyond that superficial glance, to convert that glance into a more concentrated gaze (Sulter, 1992: 264).

Together with the use of annotation, another way that Sulter promotes this ‘concentrated gaze’ in Significant Others is through the rips, tears and creases in First word ‘gaga’, Memories of veils and kisses and Maud Elsie. Rather than creating new prints from original negatives, Sulter re-photographed the images, preserving their signs of use and interaction. These marks convey a sense of the photographs being treasured: periodically unfolded to be looked at, then refolded for safekeeping. While the Significant Others images in some respects conform to the socialising, potentially disciplining effects of the family album, Sulter’s selection, annotation, and attention to the evidence of interaction on their surfaces testifies to the possibility of using photography to (re)construct the self in a positive, empowering way. The use of scale, whereby small, private images are blown-up for public display, underscores this valuation of the often overlooked or ostensibly everyday.

Sulter continued to work with the ideas in Significant Others well beyond 1993, notably through Sekhmet in 2005 at the Gracefield Arts Centre in Dumfries. Like Zabat, it took the form of both a poetry collection and an exhibition, incorporating images relating to Significant Others with photographs from Sulter’s Ghanaian family archive. In addition to gathering family images through research in Ghana, Sulter also made the film My Father’s House (1999), which draws on footage from her father Claude Ennin’s funeral. For Cherry, these works expand the concerns of Significant Others to address ‘the distances between families, cultures, countries and continents,’ and reflect on ‘appearance, legacy, inheritance, kin and culture, the shared and distinctive nature of family archives.’[iv] Building on the important exhibition Maud Sulter: Passion at Streetlevel Photoworks in Glasgow in 2015, the acquisition of Significant Others by St Andrews University Museums provides a significant prompt and opportunity for more research to be done into this deeply compelling series, both in terms of its interaction with other aspects of Sulter’s prolific artistic, curatorial and poetic output, and its trenchant engagement with photographic histories, the construct of the family album, histories of diaspora, black feminist thought and artmaking, and the connections between Scotland and Africa.

References

Cherry, Deborah (2015). ‘Poetry – In Motion.’ In Maud Sulter: Passion, pp. 8–19. London: Altitude Editions.

Cherry, Deborah (2013). ‘Image-Making with Jeanne Duval in Mind: Photoworks by Maud Sulter, 1989–2002.’ In Women, the Arts and Globalization: Eccentric Experience, edited by Marsha Meskimmon and Dorothy Price, pp. 145–68. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Himid, Lubaina (2013). ‘Exhibiting Black Women’s Art in the 1980s.’ In Politics in a Glass Case: Feminism, Exhibition Cultures and Curatorial Transgressions, edited by Angela Dimitrakaki and Lara Perry, pp. 84–9. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Sulter, Maud (1992). Interview by Mark Haworth-Booth. History of Photography 16, no. 3, pp. 263–66.

Sulter, Maud (1991). ‘Passion: Blackwomen’s Creativity,’ Interview by Ardentia Verba. Spare Rib, no. 220 (February), pp. 6–8.

Further Reading

Aikens, Nick, and Elizabeth Robles, eds (2019). The Place Is Here: The Work of Black Artists in 1980s Britain. Berlin and Eindhoven: Sternberg Press and Van Abbemuseum.

Cherry, Deborah (1998). ‘Troubling Presence: Body, Sound and Space in Installation Art of the mid-1990s.’ RACAR: Revue d’art canadienne/Canadian Art Review 25, no. 1/2, pp. 12–30.

Ewan, Elizabeth, Rose Pipes, and Jane Rendall (2018). ‘Maud Sulter.’ In The New Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women, https://search-credoreference-com.ezproxy.st-andrews.ac.uk/content/entry/edinburghsw/sulter_maud-/0?institutionId=2454

Grant, Catherine (2019). ‘A Letter Sent, Waiting to Be Received: Queer Correspondence, Feminism and Black British Art.’ Women: A Cultural Review 30, no. 3, pp. 297–318.

Himid, Lubaina (2011). Thin Black Line(s). London: Tate Britain.

Mabon, Jim (1998). ‘Europe’s African Heritage in the Creative Work of Maud Sulter.’ Research in African Literatures 29, no. 4, pp. 149–55.

Marsack, Robyn (2008). ‘Maud Sulter,’ Obituary. The Herald Scotland, 22 March, https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/12460747.maud-sulter/

[i] Deborah Cherry, ‘Image-Making with Jeanne Duval in Mind: Photoworks by Maud Sulter, 1989–2002’ in Marsha Meskimmon and Dorothy Price (eds) Women, the Arts and Globalization: Eccentric Experience (Manchester University Press, 2013), p.157.

[ii] Lubaina Himid, ‘Exhibiting Black Women’s Art in the 1980s’, in Angela Dimitrakaki and Lara Perry (eds) Politics in a Glass Case: Feminism, Exhibition Cultures and Curatorial Transgressions (Liverpool University Press, 2013), p.89. Emphasis in original

[iii] Maud Sulter, ‘Passion: Blackwomen’s Creativity,’ Interview by Ardentia Verba, Spare Rib, no.220 (February, 1991), p.8.

[iv] Cherry, ‘Poetry—In Motion’, in Maud Sulter: Passion (London Altitude Editions, 2015), p.19.

[1] Deborah Cherry, ‘Image-Making with Jeanne Duval in Mind: Photoworks by Maud Sulter, 1989–2002’ in Marsha Meskimmon and Dorothy Price (eds) Women, the Arts and Globalization: Eccentric Experience (Manchester University Press, 2013), p.157.

[1] Lubaina Himid, ‘Exhibiting Black Women’s Art in the 1980s’, in Angela Dimitrakaki and Lara Perry (eds) Politics in a Glass Case: Feminism, Exhibition Cultures and Curatorial Transgressions (Liverpool University Press, 2013), p.89. Emphasis in original

[1] Maud Sulter, ‘Passion: Blackwomen’s Creativity,’ Interview by Ardentia Verba, Spare Rib, no.220 (February, 1991), p.8.

[1] Cherry, ‘Poetry—In Motion’, in Maud Sulter: Passion (London Altitude Editions, 2015), p.19.