On 18 October 2020 Fife artist Carolyn Scott and art historian Jeremy Howard met up to discuss the David Peat (1947-2012) photographs in the Boswell Collection and their context. Carolyn was born in the same year as Peat (1947) and her own photographs of Newcastle (Elswick), like Peat’s of Glasgow (Maryhill and Gorbals), were taken in 1968 and are now in the University of St Andrews Library Photographic Collection.

While focussing on Peat and his approach, we also drew upon his context, including the relationship of his urban street photography to that of his contemporaries, i.e. Scott herself, Joe McKenzie (Dundee), Oscar Marzaroli (Glasgow), and Aase and Peter Goldsmith (Glenrothes). In addition, we considered a further dynamic with mid-20th-century forerunners such as Bert Hardy (e.g. Glasgow), Edith Tudor-Hart (e.g. Dublin) and her brother Wolf Suschitzky (e.g. Dundee and London), as well as the painter Joan Eardley (Glasgow). We even branched out to a relationship with 1930’s social documentary photographs by Dorothea Lange (USA) and Helen Muspratt (Wales) as well as the later ‘concerned photography’ of Sebastião Salgado and Franki Raffles, much of the latter also being entrusted to the University’s care. And then we pondered the appeal of black-and-white. What is it that it does that colour does differently? Something to do with nostalgia, aesthetics, neuronic reaction? Age-old questions no doubt, but ones the answers to which neither of us knew.

The five Boswell Collection photographs are reproduced in An Eye on the Street: Glasgow 1968, a small book celebrating the series to which they belong that was published in 2012, the year of Peat’s death. Carolyn had bought the book at Peat’s retrospective exhibition, An Eye on the World, when it showed at the Dovecot Studios, Edinburgh, in 2013. We considered the book’s works along with the 180 Glasgow and 178 Newcastle photographs that have been digitised as respective parts of the David Peat and Carolyn Scott Social Documentary Photographic Collections of the University.[i] ‘Reading’ these images together a sense of narrative began to emerge, backed as it was by a certain realisation of how Peat both framed and empathised with his subjects.

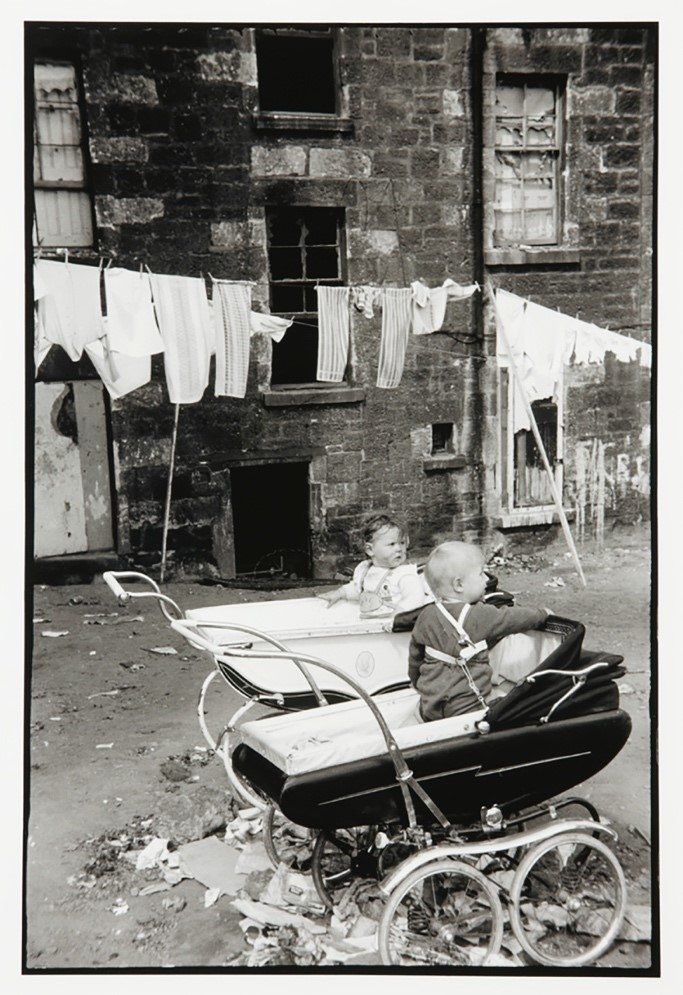

We first noticed the obvious: all five of the Peat photographs in the Boswell Collection are black-and-white images featuring children in areas of multiple deprivation, three from the Gorbals, two from Maryhill. The first of Gorbals, Back Court, is of a pair of babies in prams set within a scene of apparent squalor: viewed in vertical, cropped, format, the infants are caught between the grey stone façade with broken windows and low, doorless, entrance of the tenement block behind them. Rubbish collects around their pram wheels. Despite the pervasive wretchedness and feeling of abandonment, Peat captures something fundamentally humane: the infants, while strapped in and on their own, are decently clothed and sit up to gaze, with harmonised curiosity, at something beyond the picture frame. Plus their prams look stylish, new and pristine, and there are clean shirts and towels drying on washing lines.

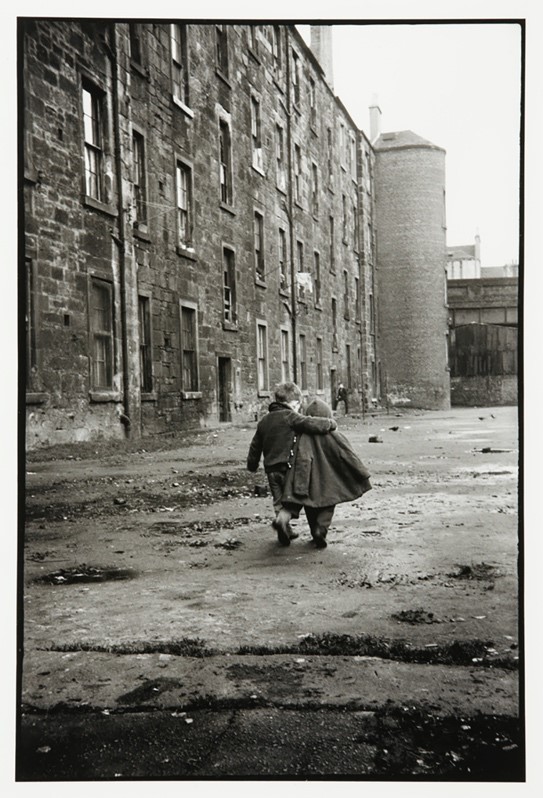

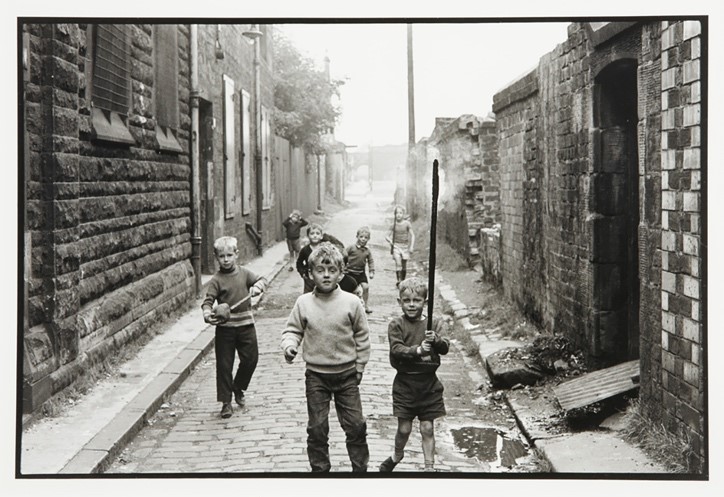

As with the other five images, this one derives from a set in which alternative views of the infants and several young children are found. Some focus on boys with toy guns while others adopt higher, more distant, viewpoints which reveal that a good number of the four-storey tenements had well-kept windows with neat lace curtains. We considered how these connected with the other two of the Gorbals in the Boswell Collection, i.e. Comforting Arm and Back Lane, these being chosen for the back and front covers of An Eye on the Street respectively. Both convey a similar sense of community. So despite the poverty children are depicted finding their own way on the street, one caring for another, others finding makeshift playthings from the debris of the derelict backyards among which they play.

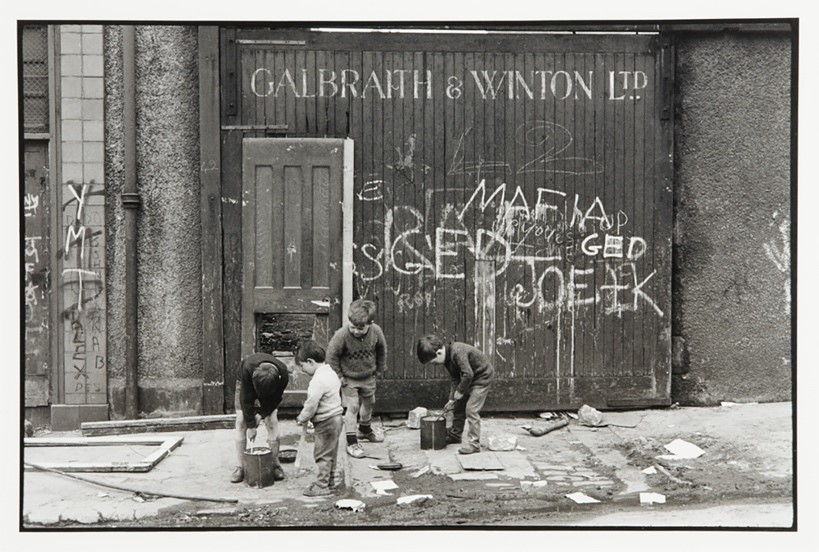

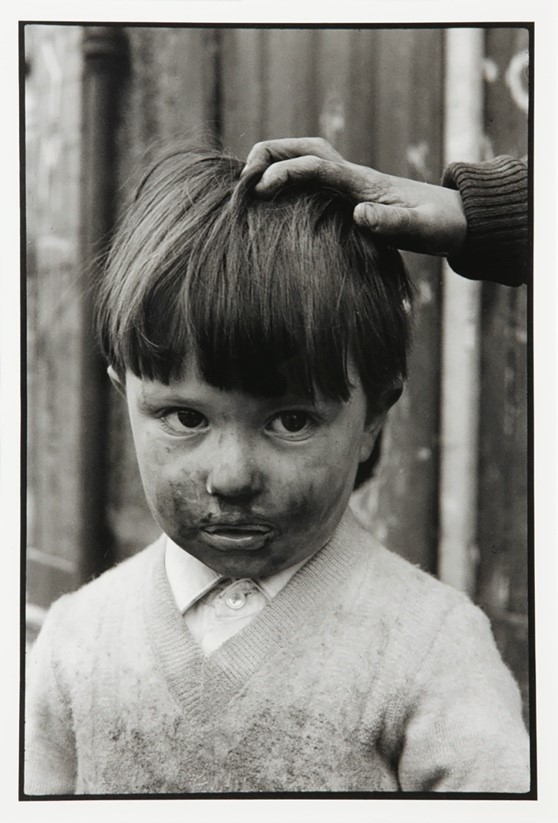

But it was not the Gorbals photographs that we dwelt on. Instead we turned to the two of Maryhill: Paintstore and Boy. These derive from a set of at least 11 photographs taken in front of the old Galbraith & Winston works. How perfectly they make a statement about art and time. Little did the boys in the photographs know that their community was about to be uprooted and dispersed, their homes, as well as whole streets, demolished to make way for the M8 motorway and ‘regeneration’.[ii] So they play on the neglected pavement, stirring and pouring paint from tins they have presumably discovered through the broken panel of the door behind them. Their street art is freer, more subversive, enjoyable and collective than that of the CIA pawn Jackson Pollock whose act of splashing paint onto horizontal surfaces they unknowingly mimic. By employing a mix of distance and close-up Peat tells the story of their painterly escapade as well as their encounter with his lens. Set against rectangles containing the logo of Galbraith & Winton, who had actually been highly skilled and much sought after monumental sculptors, marble cutters and tilers founded in Victorian Glasgow, along with abundant graffiti, we decided that this Paintstore leaks art on many levels. To think that the demolition-marked premises which they have raided for their creative supplies had been the place of making, eighty-eight years earlier, of marble baths and a fountain for Tsar Alexander II of Russia’s most extravagant imperial yacht, Livadia, that was built in Govan. And that behind that large sliding door backdrop to the boys ‘all the marble and mosaic, the [still extant] ‘chief glory’ of Glasgow City Chambers’, had been executed by the company’s craftsmen some ten years later.[iii] The boys’ performance could not have been better placed. Peat knew. His children artists of 1968 revel in their creative illicit play, the three taller boys, as revealed by the other photographs, also caring for the younger lad who Peat turns into his grubby-faced Boy. It is one of those boys’ hand that gently strokes the hair of Boy. And so this little child becomes an icon. His face and shoulders and the other’s hand fill the picture space. He gazes out, solemnly, beyond us. Sheepish, and on one occasion smiling, Peat brings him to the fore, his look more doubtful than the others, his dark hair, light sweater and neatly buttoned shirt and carefully tucked in collar, setting him apart in his nervousness from his more motley, confident friends. Who are these boys? Where are they now? They deserve to know how they have been, and continue to be, objectified.

Browsing through Carolyn’s photographs during our pondering of Peat, we noticed how, at almost exactly the same time, she had approached something equally iconic in her capturing, for instance, of a little girl with tousled hair and dirty clothes, as well as a small boy with shovel, on the streets around Elswick Road, just west of Newcastle city centre. So then we considered what it was that drew her, Peat and their ilk to record and interpret such subjects, especially since the late 1960s are often perceived as times of new prosperity and flamboyant fashion. Well, it probably comes down to empathy, and the fact that poverty is picturesque. And so we feel compromised, even now in this continuation of our conversation. For our eyes are those of outsiders, the privileged ones with artificial lenses, pens, computers. And we are feeding off those anonymous subjects for whose benefit? So while some of the children show pride and relish in finding themselves the centre of momentary attention, none of them have agency. Many could well still be alive, all of them being younger than us. We wished we could take the images back to the people and places, hang them up on railings and walls (the nearby shopping, health and leisure centres, and schools, for example) to see if folk, memories and connections could be traced. We’ve done it before (together with colleague Andrew Demetrius), in October 2018, in an empty retail unit in the Kingdom Centre, Glenrothes, with the Goldsmiths’ and press photographs of the sixties and seventies, reminding many passers-by of years and friends gone by. That this happened simultaneously with photographer Paul Duke attaching to the railings of St Andrews’ most expensive residential street, The Scores, his No Ruined Stone series, marking life (but, significantly, not that of the children) on the deprived Muirhouse estate of Edinburgh where he was (happily) brought up, suggested to us that such creative documentation is well served by these ‘alternative’ means of outreach and exposure.[iv]

Yet is it too raw when it is contemporary? We wondered whether waiting for 40 or 50 years (as Peat and Carolyn did with the public release of their photographs) can help overcome issues or deepen understanding of loss and value. And that also made us wonder about the loss of innocence of our times. No more can such photographs of children be taken. There will be no such record as Peat’s and Scott’s of youngsters spontaneously snapped on the Glasgow and Newcastle streets today. We felt conflicted. On the one hand, of course, we realise the need to protect, not least since exploitation and abuse are in close proximity. Yet, on the other hand, the shroud of suspicion divides. We considered how we would feel if we ourselves and our neighbourhoods were photographed by people we did not know for reasons we did not know. Sometimes troubled, sometimes indifferent, was our best answer. We considered how agency, rights and consent may be shared. And how insidious othering or exoticising could be avoided. We worried about whether Salgado is patronising, whether we are and Peat was. And yet we know we want to support diverse cultures and folk coming together, and we realise that photography can be one of the most powerful tools for this. We don’t want everything controlled by external authorities, we want humanity to prevail. The streets belong to all of us, so being out on them makes us fair game. And if we’ve handed over the right for our movements there to be recorded by surveillance cameras, as we become the most surveilled society in the world, surely we should preserve the right to ourselves photograph others as the actors we chance to mingle with on the street.

While Dr Tom Normand’s remarkable book Scottish Photography: A History (2007) included a few words on Marzaroli and McKenzie, and reproduced a small selection of images of (mostly anonymous) children, if Normand goes for a new edition will there be room for the likes of Peat, Scott and the Goldsmiths as photographers of poor, but, to a certain extent, free childhood? Will there be scope for inclusion of children photographers (including those using their phones)? How will the lives of contemporary youngsters be visually conveyed and compare with those of their forebears? And how will fair recompense and acknowledgment work? Familiar questions for photography history no doubt, but more broadly relevant to society, we felt. It was during Normand’s long period as advisor to the Boswell Committee that the Peat photographs were acquired for the collection. As such, with the superb qualities of eye, composition, craft and, dare we say, beauty they possess, he’s on their case. So we must hope, for society’s sake as much as art’s sake, that whatever the ups and downs, pros and cons, the variety of street life and its photographic representation, will endure… Are we naïve and nostalgic in cherishing, as their place in the Boswell Collection suggests we should, what seems to be the open-minded, straightforward, honesty of the relationship expressed between Peat and his Maryhill-Gorbals subjects? Answers on a photograph please.

[i] See: Carolyn Scott Rye Hill Social Documentary Photography Collection, Special Collections, University of St Andrews, 1968, https://collections.st-andrews.ac.uk/search/?query=ParentIRN:633423&form=grid&mode=query&query_type=query_and&sort=metaID and https://collections.st-andrews.ac.uk/search/?form=grid&f.Collection%7CCollectionTitle[]=Carolyn+Scott+Rye+Hill+Social+Documentary+Photography+Collection&query=carolyn+scott&profile=_default&num_ranks=50&collection=uofsa-web-sc-photo (accessed 18 October 2020).

[ii] The site was 48 Balnain Street, now between Unity Place and Braid Square, just north of M8 Junction 17. The Galbraith & Winston building was photographed in 1967 by John R. Hume, then a lecturer in Economic History at the University of Strathclyde, see: https://canmore.org.uk/collection/596995 (accessed 19 October 2020).

[iii] See https://www.mackintosh-architecture.gla.ac.uk/catalogue/name/?nid=GalWin (accessed 20 October 2020).

[iv] See Paul Duke, No Ruined Stone, Stuttgart: Hartmann, 2018.

Author Details:

Carolyn Scott has a Masters in Fine Art from Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art, Dundee (2010). She principally works as a photographer, filmmaker and installation artist. See: http://www.carolynscottimages.com/. Her most recent film (with Andy Sim) is Return to Brownsbank, featuring author James Robertson talking about Hugh MacDiarmid (2020).

Jeremy Howard is Senior Lecturer in the School of Art History, University of St Andrews. He specialises in 19th– and 20th century art, architecture and design, and has a particular interest in the relationship of education and art. He is currently completing a book focussed on Fra and Jessie Newbery’s ‘Serbian’ turn, its working title being: ‘The Art of Balkan Fabrications and Forgotten Distaff Sides’.

[1] See: Carolyn Scott Rye Hill Social Documentary Photography Collection, Special Collections, University of St Andrews, 1968, https://collections.st-andrews.ac.uk/search/?query=ParentIRN:633423&form=grid&mode=query&query_type=query_and&sort=metaID and https://collections.st-andrews.ac.uk/search/?form=grid&f.Collection%7CCollectionTitle[]=Carolyn+Scott+Rye+Hill+Social+Documentary+Photography+Collection&query=carolyn+scott&profile=_default&num_ranks=50&collection=uofsa-web-sc-photo (accessed 18 October 2020).

[1] The site was 48 Balnain Street, now between Unity Place and Braid Square, just north of M8 Junction 17. The Galbraith & Winston building was photographed in 1967 by John R. Hume, then a lecturer in Economic History at the University of Strathclyde, see: https://canmore.org.uk/collection/596995 (accessed 19 October 2020).

[1] See https://www.mackintosh-architecture.gla.ac.uk/catalogue/name/?nid=GalWin (accessed 20 October 2020).

[1] See Paul Duke, No Ruined Stone, Stuttgart: Hartmann, 2018.