How did you become involved in the Boswell Collection, what was your role?

This was a generous gift from the Boswell family, and it came as a pleasant surprise for all of us involved.

In fact, it wasn’t presented to the School of Art History but was directed towards the St Andrews Scottish Studies Institute. SASSI was an interdisciplinary group that offered a degree in Scottish Studies. These degrees encompassed aspects of Scottish Literature, Modern and Medieval Scottish History and Art History, all focussing on aspects of Scotland’s contribution to world culture. I was the art historian in the group. Douglas Dunn, the eminent poet and now Emeritus Professor of English, was the Director of the Institute and suggested that the gift be used to purchase Scottish art. It fell to me to become the coordinator for the collection and its development.

Broadly, I was encouraged to conceive of the shape and nature of the collection, to source artworks, to suggest possible acquisitions and to enact the decisions of the Boswell Committee. Little did I know then that this would engage nearly twenty-three years of my life, but it was always a positive experience

Did you know Harry and Margery Boswell? If so, can you tell us anything about their vision for the collection and its place at the University?

Sadly, Harry had passed on by the time the collection was created. I did meet Margery early in the process, but she too left us. In my opinion the collection is their memorial, I hope a worthy memorial.

For the most part I was involved with Bruce Boswell, and his siblings in the extended Boswell family. It became clear in our early discussions that they were a generous and empathic group. Also, the whole family was fiercely proud of their Scottish roots and gave expression to this in many forms, not least in their gifts to the university.

Bruce reminded us that Harry, in particular, was an avid collector of Scottish art. He frequented the auction houses in Edinburgh and Glasgow during the 1960s and had acquired a fine collection of historical and contemporary works. The collection at the university would recognise and expand this enthusiasm.

Of course, I was familiar with the art collections at the Talbot Rice Gallery in the University of Edinburgh and the Hunterian Gallery at the University of Glasgow. These are venerated and historic collections. In comparison St Andrews held a rather random assembly of art works, most usually casually bequeathed to the university and often arriving in our collections by accident. I had no thoughts that we could compete with the established collections in Edinburgh and Glasgow, especially given their proportion of canonical works. But the continuing generosity of the Boswell family has created the foundations of a substantial collection.

Could you tell us a bit more about the process of acquisition in relation to the Collection—was there a systematic programme or was it more opportunistic?

Quite early on we settled into a format. An annual group meeting, the presentation of possible acquisitions, a discussion on the merits of works and artists, and then the business of negotiating the purchase.

In truth, it was all a bit more complicated than this sketch.

The committee might be fluid, and changed over the years. Essentially, it was composed of family members, most usually those who were visiting Scotland at the time of the meeting. Bruce, however, was ever the constant figure at our assemblies. There were also those friends of the family who looked after their interests in Scotland: Frank Quinault, their first link to the university and the convenor of the meetings for the majority of its seminal years; David Buchanan, the family lawyer who both understood the finances and also had a fair knowledge of Scottish art; Ian and Marjorie Appleton, the architects who worked on the renovation of the family castle in Fife, they had an exceptional knowledge of the Scottish art world; and, Douglas Dunn who had an intimate sense of the culture of Scotland.

I was there as the specialist in Scottish art and as someone familiar with working artists in Scotland. It fell to me, each year, to select those artists who might best grace the collection. I’d usually present four or five suggestions and give an account of each artist’s career and merits. The group would then discuss these suggestions and settle on an artist to approach. It was then up to me to negotiate the selection and purchase. In the following year I’d present the art and await the appraisal of the group. All very nerve-wracking.

But, it’s evident from this process that the collecting policy couldn’t be strictly ‘systematic’. We set, as a general rule, the notion that we would only collect works from artists who had a national and international profile. Also, where possible, artists from the historical canon. Because Scotland is a small country, and the art world is a microcosm of that limited sphere, it was the case that I was approaching artist that I knew, had written about, and that I admired. They were, often, my friends. This may seem convenient, but it actually made it all very difficult. I was asking for works that would be given to the collection at a substantial discount. In truth, I was embarrassed by this, but the opportunity for artists to be represented, in perpetuity, within a collection held at the University of St Andrews was a significant draw.

In the main it all went well. I believe that I managed to collect works at the best cost. On reflection, I may have on occasion been compelled to negotiated at the market value, and this was certainly the case when I had, sometimes, to mediate with artists’ dealers but generally we attained an optimum trade.

Given this situation, and my own position in the Scottish art world, I know that the collection was, initially, skewed towards those artists with whom I was most familiar. We are all of us bound to generational networks, and I was lucky enough to be connected to that group of figurative artists who developed an international profile in the middle years of the 1980s; most especially those artists who gained recognition in ‘The Vigorous Imagination’ exhibition held in the Scottish Gallery of Modern Art in the summer of 1987. In which case we tended to collect figurative and narrative works by individuals like Calum Colvin, Ken Currie, Adrian Wisniewski and Steven Campbell. Alongside these luminaries there were other eminent artists from an earlier generation including Barbara Rae, Alan Davie, John Bellany, Sandy Moffat and Will Maclean. Will would later join me on the committee and his expertise was invaluable. From the proceeding generation I was delighted to purchase pieces from Alison Watt, Callum Innes and Toby Paterson.

It was always an ambition to hold pieces of historical interest, and especially from the period of Scottish Modernism, and so images by J. D. Fergusson, Agnes Miller Parker and William McCance were important additions to the collection.

Photography, too, was an interesting dimension and the pieces by Harry Benson and Patricia Macdonald form the seeds of a representation of contemporary photographic images that might complement the Photographic Collection held by the university.

So, the collection was gathered in a formal process but it was not planned in a systematic manner. Rather, it was determined by the selections of the committee, the availability of artist’s work, and the possibility of connecting with the artist in negotiation.

Some of the first works purchased by the Fund are part of the Thursday Child series. Could you provide any information about them and how they came to be part of the Collection (or nearly didn’t!)?

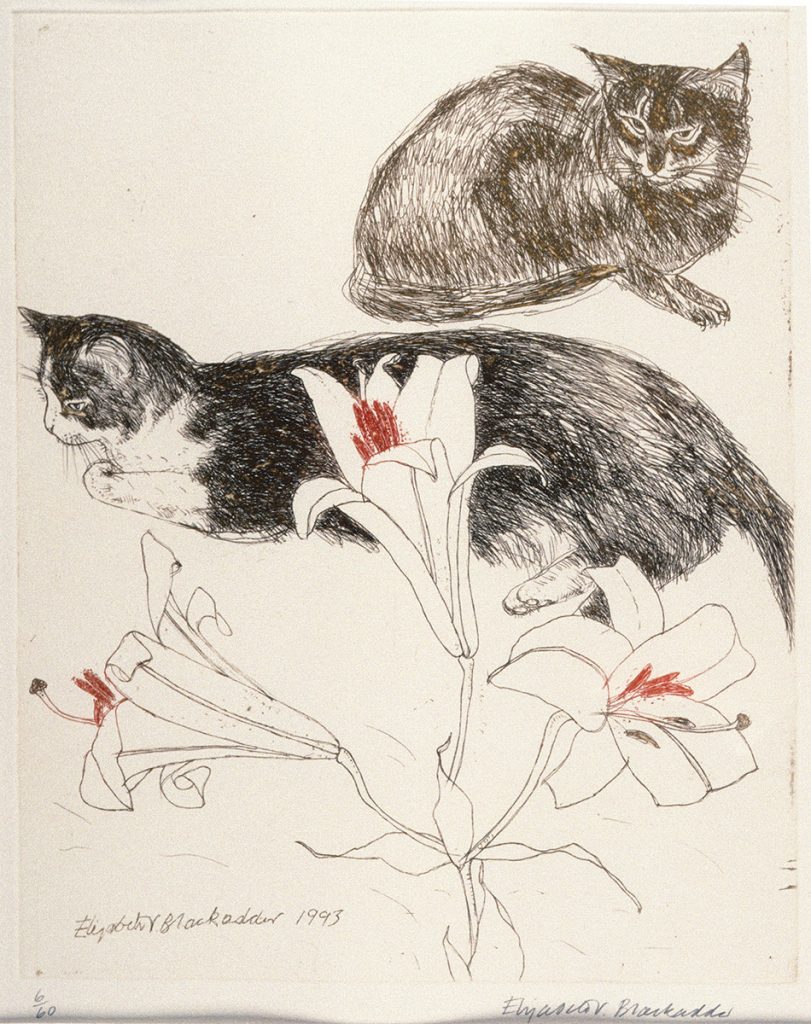

‘Thursday’s Child’ was a portfolio of prints that was available, in a limited edition, from the Dundee Printmakers Workshop. It was the first purchase for the collection. I was keen to purchase this portfolio for it included many images from The Edinburgh School, that group who were highly represented in Harry Boswell’s private collection. And so, prints by Elizabeth Blackadder and John Houston were important in this context. These were complemented by the works of younger artists including Margaret Hunter, June Redfern, Elspeth Lamb, Elaine Schemilt and Paul Furneaux. It was a way of initiating the collection with a group of images that would give a broad representation of contemporary Scottish art, and might be displayed collectively.

Now, in those days, the physical collection of works from artists, their representatives, and dealers was nearly always my responsibility; I travelled over half of the country visiting studios and galleries to accept the works and to return them to St Andrews, by car. In this process, ‘Thursday’s Child’, the first item in the collection, was lost. I say lost, but I had placed the portfolio on the roof of my car, turned and spoken to someone, then drove way with the portfolio still on the roof. Not my finest hour.

When I realised what I’d done I was distraught. I did that classic thing. I went to the local police station and asked if anyone had handed in a red box with the words ‘Thursday’s Child’ embossed on the lid. Amazingly, a laughing officer reached under the counter and handed me the box. It was flattened and with a tyre track beautifully impressed across the embossed lettering. Those familiar with Robert Rauschenberg’s 1953 work titled Automobile Tire Print will understand. Anyhow, I went back to the Dundee Printmakers Workshop and showed them the evidence of my hapless incompetence. To their eternal credit they simply gave me a replacement portfolio. But true, this was not my finest hour.

Your involvement has been central to the success and growth of the Collection, but you are also integral to it in other ways. Can you tell us about Steven Campbell’s portrait of you? How did that come about, what’s the story behind it?

Well, this was neither planned, nor desired on my part. I didn’t know Steven Campbell, but I knew he should be approached for the collection. He had a stellar career, in New York city, during the 1980s and was lionised on his return to Scotland late in that decade. I approached him, by letter, with a modest budget and suggested we would like a print for the Boswell Collection. He was fine with this, but shortly after he called me and said he wanted to paint my portrait. I was temperamentally reluctant to agree this but Steven was a very forceful character. He visited me at home and took away some photographs. It happens that the one he used in the portrait was an early 1980s photo of me, taken by Calum Colvin, in Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art. So, the young man in the painting is a tyro teacher in the art college; looking wide-eyed and terrified.

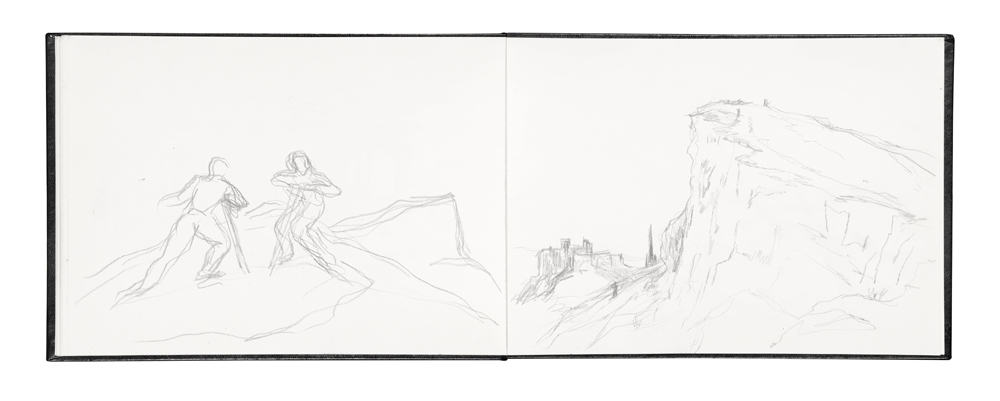

The constructed artwork is a typically visionary and vivid work by Campbell: by turns comic and ironic, inventive and challenging, benign and acerbic. I recall that he would telephone me, at odd hours, asking questions about my work and opinions. He also said that he wanted the image to resemble a poster, left to deteriorate in a Parisian café, and so embodying a passage and a history. In this way the work incorporates a stylised version of the Colvin photograph with a negative shadow behind this representing my image in the present time of the portrait. Also, a number of sketch books and other objects are pressed into the picture. The sketch books are quite detailed and show his workings and thoughts. There is a host of other esoteric symbols and insignia, and, of course, my name emblazoned on the image.

After some negotiation we bought it into the collection. I must admit it is a bit of a burden for it will be difficult to conserve. Still, it’s one of the very few portraits that Steven Campbell ever undertook during his lifetime.

The focus of the Collection is Scottish art. How did you think about ‘Scottishness’ when selecting works for it? What is distinctive about Scottish art?

Of course a question like this is fraught with political and cultural issues, particularly in the current climate. For me Scottish art was, and is, simply art from Scotland; in the broadest sense.

It is the case that as I emerged as an academic certain national discourses were prevalent within the discipline. So much so that the Royal Academy, in London, ran blockbuster exhibitions on the subject of ‘German Art in the 20th Century, ‘Italian Art in the 20th Century’, and ‘British Art in the 20th Century’: indeed ‘The Vigorous Imagination’ exhibition was a riposte to this last presentation which had barely represented Scottish art in the context of Britishness. In some senses, then, the collection was designed to foreground artists whose work was marginalised or under-represented in the wider context.

But, it was never the case that artists were obliged to be Scots, or to live and work in Scotland. They should only, in their biography, training, or output have some meaningful connection to Scotland.

Given this open and fluid sense of Scottish art it is near impossible to give a ‘definition’ of the field. Indeed, I would be chary of this kind of essentialism. It is the case that many of the works I was engaged in collecting had connections to Scottish history, cultural mores, and national characteristics, but this was often secondary to their being simply fine works of art by eminent artists.

Moreover, I’m deeply sensitive to the way that the discipline of art history has developed in the contemporary period. The kind of ‘national discourses’ I have spoken of are now suspect in the academies. Issues of globalisation, and more importantly the debates surrounding the decolonisation of the curriculum have impacted upon these types of approaches. The challenge in the future will be to collect Scottish art that is attuned to these changing tropes.

What or who inspired your own interest in Scottish art? How have you applied that expertise to the Collection, as well as any insights gained from knowing some of the artists personally?

Again, this is historical; and suddenly I feel old.

I came to the discipline from a background in sociology. My interest was in art, social class and ideology. This was part of something then called the ‘New Art History’, the development of an interdisciplinary approach that eschewed traditional methodologies and looked to view art within the frame of critical theory, politics, feminism, psychology and related fields of study.

In this respect, I had focussed on British art. Principally because I had no expertise in languages, but also because I was interested in the ways that modern(ist) British artists varied in respect of the political debates of the 1930s. Consequently, I wrote my doctoral thesis on the ways in which Wyndham Lewis’s ‘fascism’ was embedded in his art.

Later this developed into a concern with Scottish art. Partly because I recognised that Scottish art was ‘lost’ within the discipline.

In fact, this became most evident in the period after the failed Devolution Referendum of 1979. Following this there emerged a desire to foreground Scotland’s distinctiveness in all kinds of areas. In art history Duncan Macmillan would publish his ‘Scottish Art 1460-1990’ and this was the first comprehensive survey of Scottish art since James Caw’s ‘Scottish Painting Past and Present 1620-1908’, published in 1908. There flowed from this not so much a torrent but at least a bubbling burn of books, articles and catalogue essays on Scottish art; I contributed to this stream and it became my specialism.

It was in this context that I tried to provide for the Boswell collection the best and most dynamic artists from Scotland in the period. Naturally, I was assisted in this by the fact that I was writing on their work, and presenting essays in their catalogues. It was a natural synergy made easier by the fact that Scotland is a small nation, and is generally collaborative in matters of culture.

What perspectives and insights can we gain from art, and how can a collection like this enrich learning and the student experience in and beyond the classroom? How did you use the Collection in teaching?

The first part of this question is impossible to answer within this context.

I can say that I frequently used the collection on my module titled ‘Post-war art from Scotland’. This allowed the students to become cognisant of the physical and tactile work, and to explore a sense of ‘making’. I fully regard this last as crucial for the study of art history.

More than this I would invite artists to speak on the module and most agreed so to do. This included artists like Alison Watt, Sandy Moffat, Ken Currie, Calum Colvin, and Will Maclean. There were others who spoke on the module, the late Maud Sulter for example, and I’ve always been saddened by the fact that she was never represented in the collection.

Given that some of the Collection is displayed in the Art History building did you feel added pressure selecting the works? What reactions have the Boswell artworks received in the School?

Ah, well, I never felt any pressure but I was aware that not all colleagues relished the selections I was making. Indeed, I was occasionally reminded that this or that purchase wasn’t wholly appreciated. These were often matters of taste but it may also be the case that, with the current concerns in the discipline, collecting ‘Scottish’ art signals too narrow a focus.

As for ‘reactions…in the School’ perhaps I’m not the best judge. Indeed, it might be a useful, not to say enlightening, exercise to undertake a survey on this subject.

- Do you have a favourite work in the Boswell Collection?

This is interesting. As I look at the collection online I see Anne Redpath’s Still Life, Abstract from 1962. Increasingly I’ve admired Redpath’s work and this is a fine example. In fact the last piece I wrote, before retiring from the university, was an essay on Redpath published in the book I edited on the collection in the Royal Scottish Academy; the book was Ages of Wonder: Scotland’s Art 1540-now. The irony is I think this work entered the collection after my tenure for during my time the work of Redpath was prohibitively expensive. Whatever, this is a fine painting.

Of course, it’s impossible to have a favourite work but let me suggest James Cumming’s Croft Table with Field Flowers and Wine Jars, 1962. When I demitted from the committee, after some twenty-two years, the Boswell’s kindly offered a sum of money to purchase a kind of ‘memorial’ piece that would recognise my service and would become part of the collection.

Cumming is a fascinating artist, and hailed from my home town of Dunfermline. An collegial figure in The Edinburgh School he was also an academician. But his style was modernist and an intriguing take on post-cubist experiment.

Anyhow, when he completed his training at Edinburgh School of Art he was awarded a travelling scholarship. Invariably Scottish artists went to France, or Italy, sometimes to Spain. Cumming chose to go and live with crofters on the Isle of Lewis, in the Outer Hebrides. This dark, sensual painting is a memory of those ‘Black Houses’ and the lives of their inhabitants. It is both local and particular in its subject, while being modern and expansive in its style and vision. Perhaps this combination is what I always aimed for in collecting Scottish art for the Boswell Collection.

Could you provide any details about the Collection’s exhibition history?

Sadly no, this is surely recorded within the archives of the university’s Museums and Collections offices. It has certainly been exhibited at various times and in differing locations, but I have no record of these events. Certainly, pieces from the collection are exhibited throughout the School of Art History.

As part of the 25th Anniversary of the Boswell Collection, we will be compiling a series of articles about the Collection. What themes would you suggest for the articles? Are there any specific artists or art historians who you would recommend that we approach to discuss the Collection?

This is difficult. I might suggest that the pool of historians working on Scottish art has contracted rather than expanded.

There are opportunities, however. It is possible to explore the collection within the context of Museum and Gallery Studies; dissertations and essays on the nature of university collections might include the Boswell Collection as an example. Equally, the issue of how the collection might be displayed, and presented in various contexts could be viewed as a fruitful topic.

Equally, I note that there are aspects of the collection that do require some thought and research. Bruce Boswell donated a portfolio of prints by William Strang, these were titled ‘Death and Ploughman’s Wife’ and were published in 1894. Strang is a fascinating figure and an exceptional print maker, he is also under-researched. This portfolio would make a great subject for a good dissertation student.

Also, Marjorie Appleton negotiated a gift of photographs by David Peat to the collection. These are ripe for serious study, most especially within the context of documentary photography by figures like Oscar Marzaroli and Joseph McKenzie. All of whom developed a vision of the Gorbals in Glasgow that was indebted to Joan Eardley’s urban works from the 1950s and 1960s; and Eardley herself would be an exceptional, if expensive, addition to the collection.

There are many opportunities here, but finding those with the time to engage with these subjects may be difficult.

What do you think is the best way to keep the collection thriving and evolving?

Change, and continual development that reflects upon the changes within the discipline, and the nature of collections in the contemporary period.

As I reflect on my contributions to the Boswell Collection I realise it’s all from another world. In truth, it is probably the case that my twenty-two year tenure was over long. The difficulty being that there was no clear succession. Oh, and that I enjoyed the connection with the Boswells and the committee.

I spoke earlier about ‘generational networks’ and much of my contribution was locked into a particular generation. These artists are still important, but the future is with a new vision. Evidently, the collection has to respond to changes within the art world and within the discipline of art history. It certainly requires a younger and sharper eye to oversee the expansion of the collection in a meaningful direction. I’m confident this is in hand.